Michelangelo, If you don’t know his work, you will, at least, know of him–next to Da Vinci, probably the most well known and influential artist of all time:

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), commonly known as Michelangelo (Italian pronunciation: [mikeˈlandʒelo]), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, poet, and engineer of the High Renaissance who exerted an unparalleled influence on the development of Western art.[1] Despite making few forays beyond the arts, his versatility in the disciplines he took up was of such a high order that he is often considered a contender for the title of the archetypal Renaissance man, along with his fellow Italian Leonardo da Vinci.

Michelangelo was considered the greatest living artist in his lifetime, and ever since then he has been held to be one of the greatest artists of all time.[1] A number of his works in painting, sculpture, and architecture rank among the most famous in existence.[1] His output in every field during his long life was prodigious; when the sheer volume of correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences that survive is also taken into account, he is the best-documented artist of the 16th century.

Michelangelo was considered the greatest living artist in his lifetime, and ever since then he has been held to be one of the greatest artists of all time.[1] A number of his works in painting, sculpture, and architecture rank among the most famous in existence.[1] His output in every field during his long life was prodigious; when the sheer volume of correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences that survive is also taken into account, he is the best-documented artist of the 16th century.

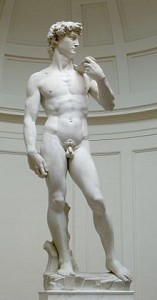

Two of his best-known works, the Pietà and David, were sculpted before he turned thirty. Despite his low opinion of painting, Michelangelo also created two of the most influential works in fresco in the history of Western art: the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling and The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. As an architect, Michelangelo pioneered the Mannerist style at the Laurentian Library. At the age of 74 he succeeded Antonio da Sangallo the Younger as the architect of St. Peter’s Basilica. Michelangelo transformed the plan, the western end being finished to Michelangelo’s design, the dome being completed after his death with some modification.

In a demonstration of Michelangelo’s unique standing, he was the first Western artist whose biography was published while he was alive.[2] Two biographies were published of him during his lifetime; one of them, by Giorgio Vasari, proposed that he was the pinnacle of all artistic achievement since the beginning of the Renaissance, a viewpoint that continued to have currency in art history for centuries.

In his lifetime he was also often called Il Divino (“the divine one”).[3] One of the qualities most admired by his contemporaries was his terribilità, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur, and it was the attempts of subsequent artists to imitate[4] Michelangelo’s impassioned and highly personal style that resulted in Mannerism, the next major movement in Western art after the High Renaissance.

Fame is one thing, renown another. When folks born hundreds of years after you know your name, you have made an imprint on the world.

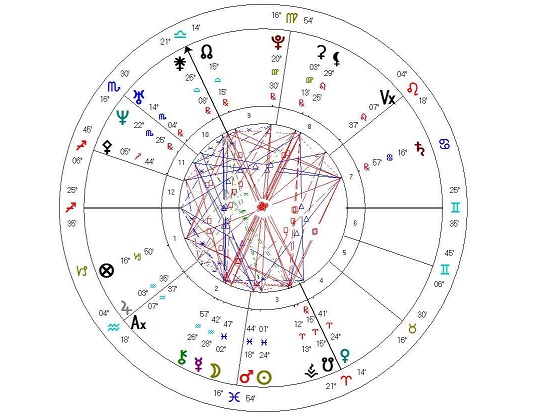

To call him an artist seems to lessen him in some way. Creator? Is that a better title? Michelangelo certainly left his stamp on Western culture. We do that by thinking outside the box, by being unique. BML is all about our unique sensitility. Here is another case of BML opposite the Moon. But BML is not only opposite the Moon, it is also opposing a tight Mercury/Chiron conjunction in the second house, which is food for thought. The greatest artist in the Western culture had Chiron in the 2nd house. ( Try to keep lamenting now, all you Chiron in the 2nd house people, who claim you can’t have any talent.) Fixed houses are about use, and the 2nd is about our use of talent. BML ensures this talent is used in extraordinary ways, even to the point of breaking. BML will drive this talent to extremes, if need be. Particularly an extreme-oriented Pisces Moon. This BML in Lilith insists on being individualistic and going its own way. It needs to communicate not what is there, but what is not immediately apparent. He once said his job was to liberate the figure from the stone. When BML is opposed the Moon we have a mind (in a larger sense of Body/Mind) and inclinations that are not common. We are more comfortable at the periphery of society. This allows us to observe. Mercury/Chiron feels limited, constrained. BML liberates Mercury/Chiron into the realms of the heretofore unseen and unknown. In the Pieta, we see suffering as almost a glorified state of grace. In the David, we see a beauty that is almost painful. It’s almost as though Lilith has turned the world’s strangeness and alienation in on itself, and learned to celebrate it. There is a Mars/Pluto opposition with the Sun involved, and he certainly had his battles, artistically and ideologically, with others, yet he made peace with the mysterious inner voice that is Lilith. BML does not thrash out once it understands it must evolve in its own time and in it’s own way. The frustrated Lilith creates chaos, the focused Lilith merely creates.